PRESENTATION-COPY OF KIERKEGAARD'S PHILOSOPHICAL MAGNUM OPUS

KIERKEGAARD, SØREN.

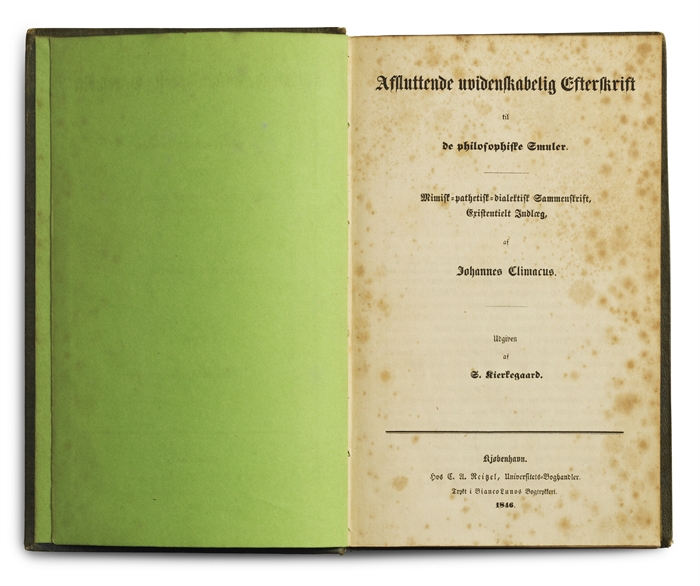

Afsluttende uvidenskabelig Efterskrift til de philosophiske Smuler. Mimisk=pathetisk=dialektisk Sammenskrift, Existentielt Indlæg af Johannes Climacus. Udgiven af S. Kierkegaard.

Kjøbenhavn, Reitzel, 1846.

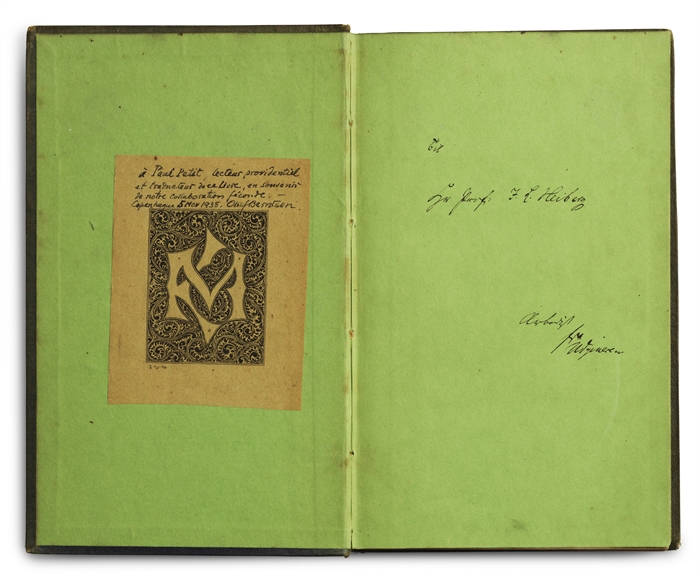

Large 8vo. X, 480 pp + (3) ff. (- i.e 1 blank + 4 pp. postscript). Gift binding of plain purpleish-brown full cloth with single gilt lines to spine. Spine and top of boards faded. A bit of wear to capitals and corners, but overall excellent condition. All edges gilt. Brownspotting throughout. A pencil-correction on p. 125 (in the word “Udødelighed”, i.e. immortality). With the book-plate of Karl Madsen to inside of front board. On this a gift-inscription from Oluf Berntsen to Paul Petit, who translated the Postscript into French, dated Copenhagen Nov. 5 1938.

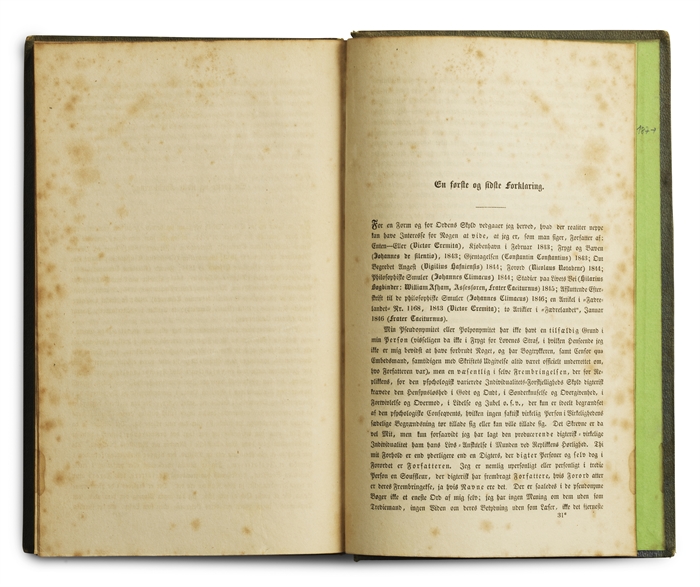

Magnificent presentation-copy (one of four known) from Kierkegaard to Heiberg of Kierkegaard’s philosophical magnum opus, inscribed to front free end-paper: “Til / Hr. Professor J.L. Heiberg / ærbødigst / fra / Forfatteren. (i.e. For / Mr. Professor / J. L. Heiberg / most respectfully / from the Author). By many considered Kierkegaard’s crowning achievement and by most philosophers, his greatest work, The Postscript, as the work is usually referred to, occupies a central position in Kierkegaard’s authorship. Not only is the Postscript arguably the most philosophically important of Kierkegaard’s publications, it is also the work that reveals one of the most important “secrets” of our philosophical giant: the authorship of not only his main work and the main work of existentialism, Either-Or, but of all of Kierkegaard’s pseudonymous writings. Apart from revealing the true identity of the author of all of the pseudonymous writings and providing the key to understanding the complicated thoughts behind the pseudonyms, the Postscript is especially famous for its dictum “Subjectivity is Truth”. The work is an attack on Hegel, especially his Science of Logic, and on Hegelianism in general. This magnum opus of 19th century philosophy marks a defining turn in philosophy, away from the system and towards subjectivity, in general terms bringing “existence” into modern philosophy. As we know, nothing that Kierkegaard did was left to chance, which is also reflected in his carefully chosen pseudonyms and everything that came with them, e.g. his presentation-inscriptions, which carefully followed the pseudonym of the book, so that he never signed himself the author, if his Christian name was not listed as the author on the title-page. This meticulousness also applied to the publication of his works, and the Postscript is arguably the most carefully planned of his works. The format of the book is large – 145 x 230 mm, and it is comprehensive – 480 pages, followed by six unpaginated pages, the last four of which contain the hugely important and carefully planned revelation of the true authorship of all the pseudonymous writings, under the headline A First and Last Explanation. The pages are left unpaginated, divided from the rest of the book by a blank leaf and printed with a smaller type than the rest, which clearly indicates for the reader that these pages are not part of the actual text, but noticeably different and worth paying special attention to. The postscript to the Postscript begins thus: “As a matter of form, and for the sake of order, I hereby acknowledge, what can hardly be of real interest to anyone to know, that I am, as people say, the author of Either/Or (Victor Eremita), Copenhagen, February 1843; Fear and Trembling (Johannes de silentio) 1843; Repetition (Constantin Constantius) 1843; The Concept of Anxiety (Vigilius Haufniensis) 1844; Prefaces (Nicolaus Notabene) 1844; Philosophical Crumbs (Johannes Climacus) 1844; Stages on Life’s Way (Hilarius Bogbinder: William Afham, the Assessor, Frater Taciturnus) 1845; Concluding Postscript to the Philosophical Crumbs (Johannes Climacus) 1846; an article in Fædrelandet, No.1168, 1843 (Victor Eremita); two articles in Fædrelandet, January 1846 (Frater Taciturnus).” (A First and Last Declaration, p. 527). This is followed by an explanation of the significance of the chosen pseudonyms, the reason why Kierkegaard chose to write under these, and what his relationship to each of them is – questions that none the less continue to puzzle readers to this day and which seem be bear the key to the understanding of Kierkegaard the man as well as his philosophical writings. This ironic Kierkegaard-title (stated as being a postscript to the Philosophical Fragments, which is approximately 1/6 of the size of the present work), has Kierkegaard’s name as the editor on the title-page, unlike all the other pseudonymous works, where his name does not appear at all, clearly showing the central position that this work occupies in Kierkegaard’s overall authorship. Exactly because Kierkegaard’s name appears on the title-page, he was able to give away presentation copies of it, unlike the other pseudonymous writings. Four presentation-copies of the work are known to exist: for Heiberg, Mynster, Sibbern, and A.S. Ørsted. Johan Ludvig Heiberg (1791-1860) was a Danish poet, playwright, literary critic, literary historian, philosopher, and quite simply the main cultural figure of 19th century Denmark. Heiberg profoundly influenced all of Danish culture within this period and must be considered the patron of Copenhagen's literati. He was very influential as a thinker in general, and he changed Danish philosophy seminally by introducing Hegel to the Northern countries. Needless to say, Heiberg also played a significant role in relation to Kierkegaard, who will comment on and refer to him continually throughout his career. As the unofficial arbiter of taste for the Danish intellectuals, Heiberg was also an inevitable recipient of Kierkegaard’s works as they were published. “There can be no doubt that Johan Ludvig Heiberg was a very important figure for the development of Kierkegaard’s thought. Heiberg’s criticism dominated an entire generation of literary scholarship and was profoundly influential on the young Kierkegaard. His dramatic works and translations are also frequently referred to and quoted by Kierkegaard and his pseudonyms… However, Heiberg was also a philosopher… His philosophical profile is clearly that of a Hegelian, and, not least of all due to Kierkegaard’s influence, this has led him to being unfairly dismissed…” (Jon Stewart in: Kierkegaard and his Danish Contemporaries I: p. (35)). Heiberg was there from the very beginning of Kierkegaard’s authorship, and although the two had both diverging personalities, diverging opinions, and diverging philosophies, Kierkegaard will have had respect for his place in society. Kierkegaard viewed himself as somewhat of an outsider, and it was of great importance to him to try and enter the famous literary and cultural circle of Heiberg. Heiberg is known for founding his own school of criticism and for his brilliant polemics against literary giants of the period. He was without comparison the most dominant literary critic of the period, and he reformed Danish theatre, introducing eg. French vaudeville to the Danish stage. Although through foreign influence, he ended up creating for the first time an actual national theatre in Denmark. “Heiberg’s success in so many different fields during such a rich period is truly remarkable.” (Jon Stewart). Furthermore, he profoundly influenced Danish philosophy and was pioneering in introducing Hegelian philosophy to the country. There is no need to stress further the importance of Heiberg in Danish society nor in his relation to Kierkegaard. But in the present context, it must be mentioned that in his critique of Hegel in the present work, Kierkegaard also mentions Heiberg. On p. 125 (pp. 143-44 of the English translation), where the pencil correction (possibly in Heiberg’s hand?) is to be found, Kierkegaard writes: “Furthermore, I know that some have found immortality in Hegel, others have not. I know that I have not found it in the system, where it is indeed also unreasonable to look for it; for in a fantastical sense all systematic thinking is sub specie aeterni, and to that extent immortality is there in the sense of eternity. But this immortality is not at all the one inquired about, because that is a matter of the immortality of a mortal, and is not answered by showing that the eternal is immortal, because the eternal is after all not the mortal, and the eternal’s immortality is a tautology and a misuse of words. I have read Professor Heiberg’s Sjæl efter Døden [i.e. The Soul after Death], indeed I have read it with Dean Tryde’s commentary. If only I had not done so, for one takes an aesthetic delight in a poetic work and does not demand that last detail of dialectical precision appropriate in the case of a learner who wants to adjust his life in accordance with such guidance...”. Himmelstrup 90.

Order-nr.: 62946