GERSON'S SEMINAL TREATISE ON RUMOR-MAKING, PRINTED BY ZELL CA. 1470

GERSON, JOHANNES (JEAN).

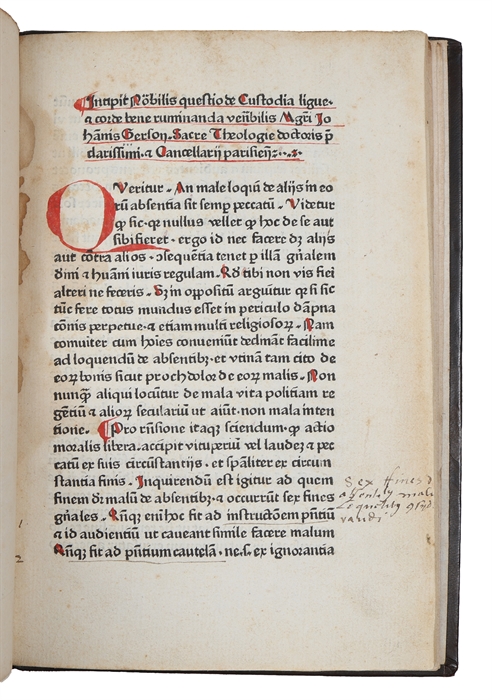

De custodia linguae et corde bene ruminanda.

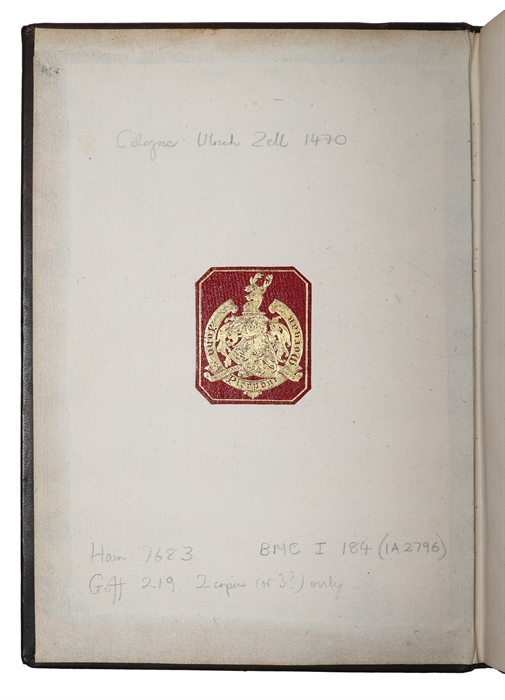

(Cologne, Ulrich Zell, ca. 1470).

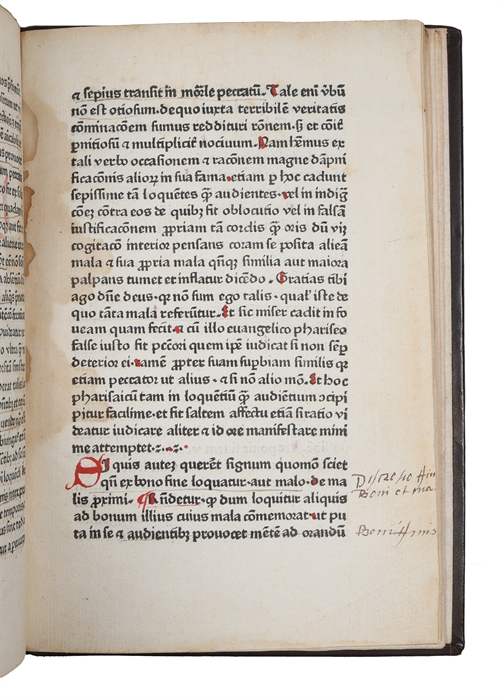

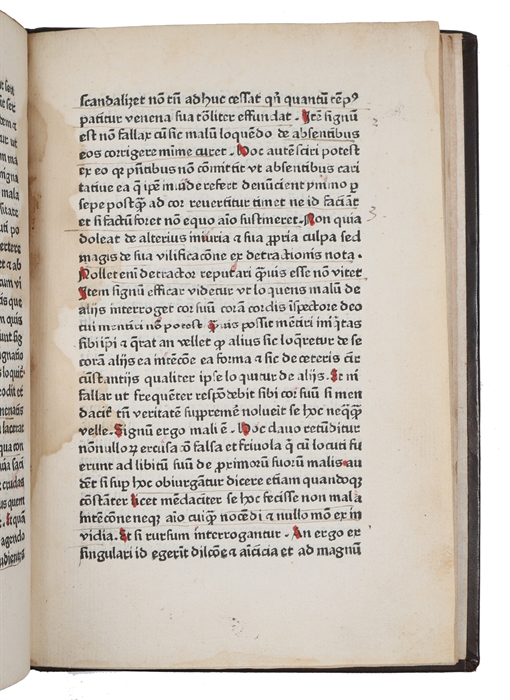

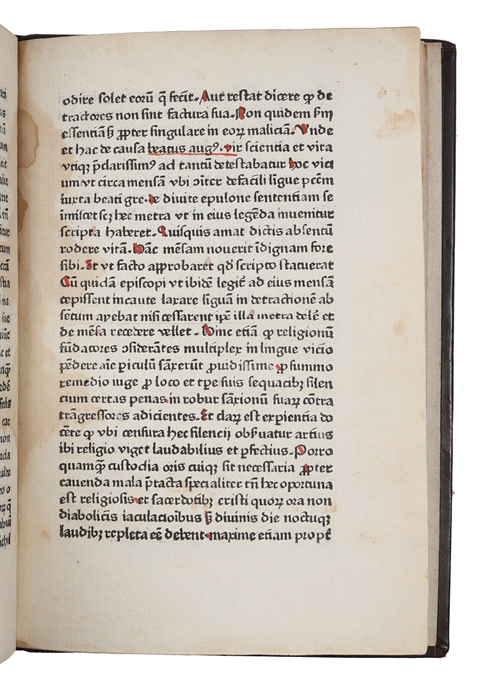

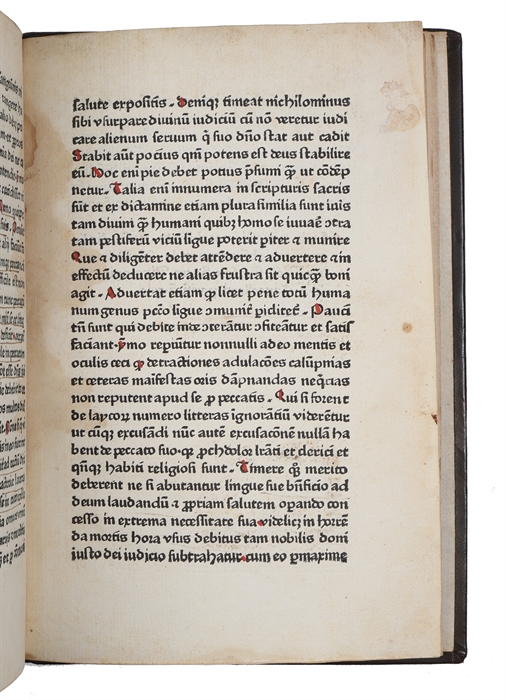

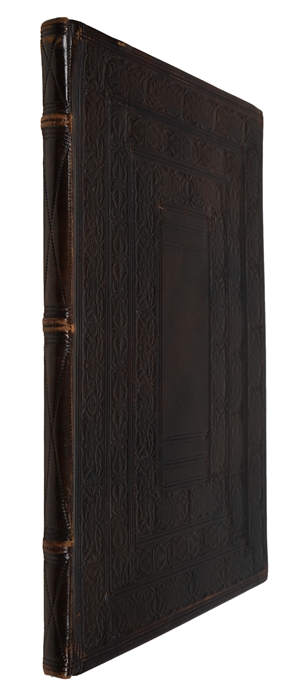

Small 4to. Beautifully bound in a later (ca. 1900) full calf binding in Renaissance style with three raised bands and blindstamped ornamentation to spine. Boards with three wide ornamental blindstamped borders inside each other. A damp stain to inner margin and a bit of light brownspotting. Early marginal annotations (some of them slightly shaved) and underlinings. 6 ff. + first and last blank. 27 lines to a page. A large, four-line opening initial in red, a two-line initial in red, paragraph marks as well as capital strokes in red throughout, and red underlinings in beginning and end. A lovely copy.

With the gilt red leather ex libris of John Pierpont Morgan to inside of front board.

Magnificent, early incunable edition, being the exceedingly scarce second edition (as a Zell-edition dated between 1467 and 1470 is considered the first - these two first editions are of equal scarcity) of this highly important tract on the moral implications of speaking ill of others in their absence, by one of the pioneers of natural right theory, Jean de Gerson, printed by the eminent first printer of Cologne, Ulrich Zell. The work, though having been overlooked for centuries, is of the utmost importance to the shaping of Western thought, both legal, religious, and moral, and it was extremely influential in its time. It appeared as many as four times around 1470 (the two first editions printed by Zell, who was the main printer of all of Gerson's works, followed by an edition by Fust and Schöffer shortly after and another one by Therhoernen) with editions following in both the 1480'ies and 90'ies. The two Zell-editions, which constitute the first appearances of the work, are distinguishable by the printing error in the first line of A1r, which says "Intipit" (the present copy - Hain 7683) instead of "Incipit" (Hain 7682). The number of early editions of Gerson's work bears witness to his tremendous popularity as a moral and spiritual authority in 15th-century Europe. In spite of being “[o]ne of the smallest and rarest of the many tracts by the Chancellor of Paris Jean Charlier de Gerson (1363-1429), which were printed by the earliest printer of Germany" (Rhodes), the work nonetheless exercised great impact. The theme of the treatise is the morality of speaking ill of others behind their backs, which has implications for, not only morality philosophically speaking, but also legally, theologically, and religiously, tying together the most important themes of Gerson’s thought. Curiosity and vanity, which are at the heart of rumor-making and speaking ill of others behind their backs, are two main intellectual vices that must be warned about in all contexts. “The reflection on vices and sins, both from the moral and the intellectual point of view, is a “fil rouge” in Jean Gerson’s production. As a theologian constantly concerned with shaping a correct theology and driven by the necessity to pursue the safety and unity of the doctrine, the Parisian Chancellor often warns his students and colleagues about the dangers connected with this misuse of rationality. (Luciano Micali: The Consent of the Will…, p. 1). “Jean Gerson (b. 1363–d. 1429; also Jean de Gerson, or, originally, Jean Charlier) was the most popular and influential theologian of his generation, the most important architect of the conciliar solution to the Great Schism (1378–1415), and the leading figure at the Council of Constance (1414–1418). He came from a family of modest means in the Champagne region of France. As a young student at the College of Navarre in Paris, he came in contact with humanist currents from Italy (he probably read Petrarch at this time), which left some traces in his writings. He first gained fame as a popular preacher in Paris in the early 1390s and then followed his master Pierre d’Ailly as the chancellor of the University of Paris in 1395. He gained international renown as a result of his leading role at the Council of Constance, which put an end to the Great Schism. ... Gerson’s wide-ranging interests extended well beyond the traditional limits of university masters, and his writings serve as a window into 15th-century life and thought. His complete works were first printed in 1483 and were frequently reprinted through the first quarter of the 16th century. Later humanists and university theologians alike claimed him as one of their intellectual fathers." (Oxford Bibliographies in Medieval Studies: Daniel Hobbins: “Jean Gerson”). In spite of his enormous influence upon his contemporaries and near contemporaries of the following century, recent centuries have witnessed little insight into his vast importance. This, however, seems to be changing, as many scholars are now gaining increasing insight into the extension of his influence. “Researchers are familiar with seeing and examining the influence of Augustine, Thomas Aquinas and other significant figures in Western intellectual history. The reception of Jean Gerson (1363-1429) — the late medieval French Church reformer, ecclesiastical leader, theologian, poet, educator and chancellor of the University of Paris — is, however, an understudied field. Gerson’s legacy had nevertheless an impact on late medieval and early modern movements and thinkers of great significance, paving the way for many developments, which still shape our existence today. He became a source of inspiration for all those involved in establishing new religious and national identities, and his name appears in both Protestant (of all branches) as well as in Catholic sources. Aside from the expected influence in theology and Church history, his ideas transformed law, jurisprudence, art, music, pedagogy, literature and even medicine. The topography of his legacy is just as broad and varied, spanning from Portugal to Scandinavia, and from Japan to Mexico. From a deeper perspective, Gerson is extremely important for understanding the religious evolution of Western civilization. Jean Gerson’s legacy provides a significant theological context where contemporary ideas such as, for example, the concept of individual right or need of palliative care, find their roots. Today, when the question of religion has retaken the central stage of our existence, an understanding of our theological background is no longer the fief of specialized researchers, but a social necessity.” (Introduction to: The Reception of Jean Gerson in Late Medieval and Early Modern Theology, Spirituality and Law. Roundtable Discussion at KU Leuven, 2018) Although commonly accepted as a seminal figure important in legal theory, even his role a a pioneer of natural right theory has been overlooked, as has his vast influence on thinkers like Thomas Moore. A 2018-conference at KU Leuven has contributed to the renewed understanding of his importance. As Yelena Mazour-Matuzevich (University of Alaska Fairbanks / Senior Fellow KU Leuven) concluded: “Before looking closely at Thomas More’s connection to the late medieval French theologian Jean Gerson (1363-1429), I could not imagine the breadth and depth of More’s dependency on his legacy as a source of scriptural narrative, moral theology or legal theory. More’s extensive knowledge of Gerson’s works is evident from the Englishman’s writings, and his admiration, already manifest in his early years, only increased as he aged, climaxing during his imprisonment in the Tower.” (The Very Special Case: Gerson & Thomas More). It was only with Richard Tuck and his "Natural Rights Tradition" from 1979 that Gerson was first really credited with his pioneering work in this field. Tuck argues that Jean Gerson was the first to describe the notion of ius as “a dispositional faculty or power, appropriated to so meone and in accordance with a right was understood in terms of an ability” and places him at the centre in the rights tradition. Thus, the guiding light of the Concillar Movement and one of the most prominent theologians at the Council of Constance was also one of the first thinkers to develop what would later come to be called natural rights theory, and he was even one of the first individuals to defend Joan of Arc and proclaim her supernatural vocation as authentic. The celebrated devotional work traditionally ascribed to Thomas à Kempis, "The Imitation of Crist" has been considered by some scholars, to be the work of Gerson, although no conclusive evidence has yet been found. "Gerson was a prolific writer, and a powerful intellectual force in a calamitous period in France’s history. A champion of his university, he strongly advocated the role of theologians in the debates which erupted when the Great Schism divided the catholic church between 1378 and 1417, as first two, and then three, claimants contended for the papacy. As a cleric, he had a strong sense of pastoral responsibility, often expressed in his more personal writings. He witnessed and bewailed France’s descent into political chaos, when the madness of King Charles VI allowed rival princes to jostle, and eventually murder, to gain their ends. In 1413 the civic and political disturbances in Paris almost cost him his life. That civic disorder, civil war, and then the Lancastrian takeover with King Henry VI of England as questionable heir to Charles VI, doubtless explains why Gerson, ever the Valois loyalist, spent his final years in a kind of exile in Lyons. Many of Gerson’s major writings deal with the Schism, and the debates over the Church’s structure which it provoked. These pushed him to argue for reform, a programme which challenged papalism by urging the authority of a general council as representative of the Church as a whole. Some of his most important work addresses such matters, and he was occasionally a key player in events, notably at Constance in March–April 1415. ” (Swanson: Review of Patrick McGuire's Jean Gerson and the Last Medieval Reformation). Hain: 7683; BMC: I:184; Goff: 219.

Order-nr.: 61471