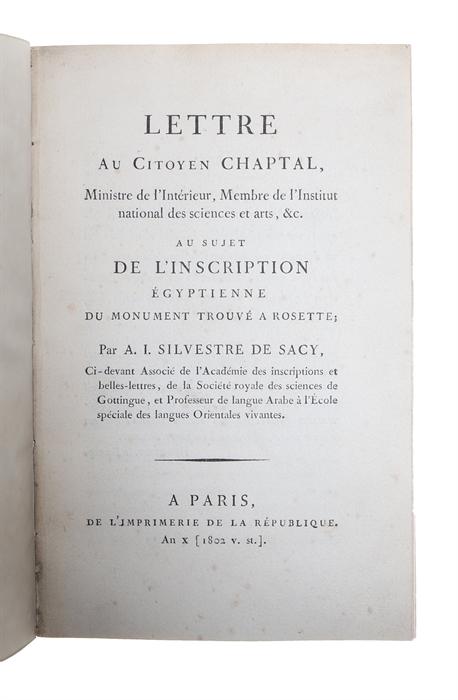

FIRST STEP TOWARDS DECIPHERING THE ROSETTA STONE AND CRACKING THE CODE OF HIEROGLYPHIC SCRIPT

SACY, SILVESTRE de.

Lettre Au Citoyen Chaptal, au sujet de l'inscription égyptienne du monument trouvé a Rosette.

Paris, 1802.

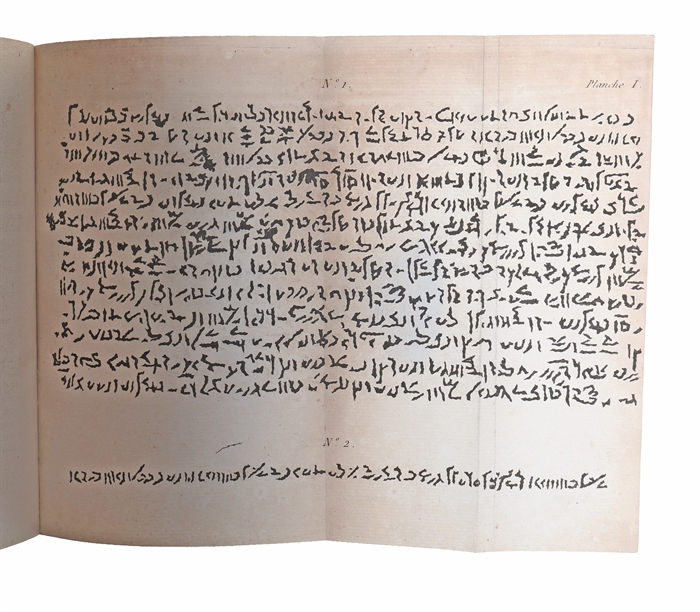

8vo. In recent marbled paper wrappers. With very light occassional brownspotting, plates slightly toned. A nice copy. Housed in a cloth clam-shell box with gilt lettering to spine. 47 pp. + 2 plates, 1 of which is folded.

The very rare first printing of the first published attempt at reading the Rosetta stone, constituting the very first step towards deciphering the Egyptian hieroglyphs. With the plates contained in this first scientific publication on the Rosetta Stone, the work also contains the first published printing of any part of the text of the Rosetta Stone. Silvestre de Sacy was a professor at the Special School of Oriental Languages in Paris, where he became the most influential teacher of Jean-François Champollion. His attempts at deciphering the Rosetta Stone proved at the end to be unsuccessful, but his proposal that the Stone's hieroglyphic cartouches might be written in an alphabet proved important, and with the present publication he laid the foundation for the correct deciphering by Champollion 20 years later. "The first scholarly publication on the Rosetta Stone was de Sacy's, pamphlet: Lettre au Citoyen Chaptal . . . au sujet de l'inscription Égyptienne du monument trouvé à Rosette (Paris, 1802). In this brief work illustrated with one transcription of a portion of the stone, the orientalist and linguist Sacy, a teacher of Champollion, made some progress in identifying proper names in the demotic inscription." (Jeremy Norman: History of Information). The Rosetta Stone, which dates back to 196 B.C was found in 1799 by French Troops and was immediately brought to England, where it has been ever since. The stone was (and is) of the utmost importance to the understanding of the Egyptian language, the principles of which were totally unknown up until this point. Because the hieroglyphic inscription on the stone is accompanied by a Greek and a Demotic one with the same contents (the commemoration of Ptolemy V's accession to the Egyptian throne), scholars would eventually be able to decipher the ancient language that had been a mystery for more than a millennium. "When military engineers discovered the Rosetta Stone in July 1799 while rebuilding an old fort in the Nile Delta, the officer in charge quickly recognised the importance of its three parallel inscriptions and sent the Stone to the savants in Cairo. "Solid attempts to decipher hieroglyphs started with the discovery of Rosetta Stone. Before being captured by the Arabs, Egypt had a native language called Coptic. There was formerly a Coptic alphabet until the 2nd century AD. However, it was replaced by Greek letters, resulting in the creation of Old and New Coptic. Therefore, the alphabet of Old Coptic became obscured over time. In 1643, long before the discovery of Rosetta Stone, Athanasius Kircher, a reputed scholar and polymath of his time, argued that the Coptic inscription represents the same language as hieroglyphs (Lee & Merrill, 1989,p . 20). Based on this argument, scholars assumed that it would be possible to decipher the hieroglyphics by deciphering the Old Coptic script. The study of the relationship between Old Coptic and the hieroglyphs was first carried out by Silvestre de Sacy, a French nobleman and scholar. He was also a mentor of the three scholars who were the successors of his research. Sacy tried to decipher the Rosetta Stone by comparing the symbols and locations of names through mathematical analysis. However, he reached a dead end after some progress and passed the study to the Swedish diplomat and scholar, Johan David Åkerblad. As an expert on New Coptic, he managed to compare its alphabet with Old Coptic, identifying some of the phonetic values and words. However, since he could not understand that Old Coptic was not entirely alphabetic, his progress was halted." (Denic Aktunz: A Warfare of Greediness over the Rosetta Stone: Deciphering Hieroglyphics).

That October, Napoleon himself, recently returned from Egypt, told the National Institute in Paris: "There appears no doubt that the column which bears the hieroglyphs contains the same inscription as the other two. Thus, here is a means of acquiring certain information of this, until now, unintelligible language.

From the moment of discovery, it was clear that the bottom inscription on the Rosetta Stone was written in the Greek alphabet and the top one - unfortunately the most damaged - was in Egyptian hieroglyphs with visible cartouches. Sandwiched between them was a script about which little was known.

It plainly did not resemble the Greek script, nor did it appear to resemble the hieroglyphic script above it, not least because it lacked cartouches. Today we know this script as 'demotic', a cursive form of ancient Egyptian writing, as opposed to the separate signs of hieroglyphic.

The first step was to translate the Greek inscription. This turned out to be a legal decree issued at Memphis, the principal city of ancient Egypt, by a council of priests assembled on the anniversary of the coronation of Ptolemy V Epiphanes, on 27 March 196 BC. The Greek names Ptolemy, Alexander and Alexandria, among others, occurred in the inscription.

de Sacy deserves credit for a useful suggestion in 1811: that the Greek names inside hieroglyphic cartouches, which he assumed must be those of rulers like Ptolemy, Alexander and so on, might be written in an alphabet, as they almost certainly were in the demotic inscription.

The same technique, he knew, was used to write foreign names in the Chinese script, which was also thought (wrongly) to have no intrinsic phonetic component." (BBC Science Focus Magazine, 2020).

Order-nr.: 61211