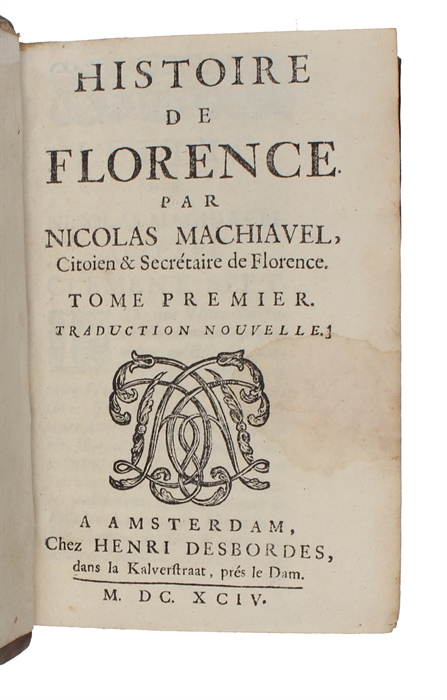

MACHIAVELLI, NICCOLO.

Histoire de Florence. Traduction nouvelle. 2 vols.

Amsterdam, Henri Desbordes, 1694.

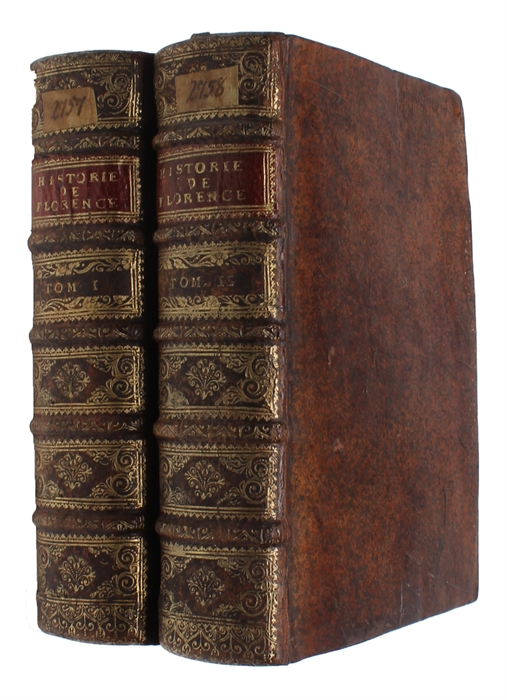

8vo. Uniformly bound in two contemporary full calf bindings with five raised bands and richly gilt spines. Edges of boards gilt. Small paper label pasted on to upper compartment of spines. A very nice set. (34), 588 pp.; 624 pp.

A fine late 17th century-edition of Machiavelli's Florentine Histories; his famous account of the political events and power struggles in Florence during the Renaissance. Essentially being a panegyric to the house of Medici, Machiavelli's work offers valuable insights into the rise and fall of political factions, the challenges faced by republican governments, and the dynamics of power in a city-state. “Although Machiavelli became the embodiment of a real "devil theory of history," there was nothing supernatural or even suspicious about his journey across the Alps. As the French translator remarked to his customers in 1544, "This Florentine merchant has voluntarily left his own country to be received into yours.... Do not be so ungracious as to refuse him citizenship. From all appearances he was welcomed with open arms, or at least open minds. Within a few years, one of his admirers declared that he was a prophet honored more in France than in his own country." (Kelley, Murd'rous Machiavel in France: A Post Mortem). Following the crisis of 1513, which involved arrests for conspiracy and torture, Machiavelli's relationship with the Medici family gradually improved. Despite the dedication of his book "Il Principe" to Lorenzo II de' Medici having little effect, Machiavelli found favor with a faction in Florence that was not opposed to him and was granted an appointment. In a letter Machiavelli expressed his dissatisfaction with his idle state and offered his valuable political experience to the new ruler. To further solidify his position, Machiavelli, adopting a somewhat courtier-like attitude, arranged for the staging of his play "Mandragola" at the wedding of Lorenzino de' Medici in 1518. In 1520, he received an invitation to Lucca for a semi-private mission, indicating that his ostracism was coming to an end. Later that year, Giulio Cardinal de Medici commissioned him to write a history of Florence. Although this was not exactly the role he desired, Machiavelli accepted it as the only way to regain the favor of the Medicis. The purpose of the work, although unofficial, was to restore the city's official historical standing. The salary for this appointment was not substantial, starting at 57 florins per year and later increased to 100. In May 1526, Machiavelli formally presented the finished work to Giulio de' Medici, who had become Pope Clement VII. The Pope appreciated the work and rewarded Machiavelli, though only moderately, and sought his support in creating a national army based on his theoretical work "The Art of War," in preparation for the War of the League of Cognac. However, Machiavelli's hopes were shattered following the Sack of Rome in 1527 and the fall of the Medici government in Florence. Soon after, Machiavelli passed away.

Although often overshadowed by his more famous 'The Prince', the present work is important in understanding Machiavelli's broader political philosophy and is an indispensable document in understanding renaissance politics in general.

The Histories constitute an essential work for understanding the political development of the late Machiavelli, and is “also an important item in modern historiography because for the first time the issue of conflict, and more precisely of urban conflict, finds itself at the heart of historical narrative (…).Infact, the Histories constitute the first attempt in modern historiography to analyze the totality of individual and collective agents and factors that allow a community to sustain itself or to founder. This analytical quality was certainly at the basis of the interest in the work outside Florence and the fact of its being translated. As Yves de Brinon explains in dedicating his ‘Histoire Florentine [the present work] to Cathrine de Medici, the case of Florence is a model for the dangers that threaten the integrity of every state and the Kingdom of France in Particular.” (Landi, A re-reading of Machiavelli).

Machiavelli visited France, representing the Republic of Florence, where he - and later his writings - exercised great influence. The Huguenot, Innocent Gentillet, whose work commonly referred to as 'Discourse against Machiavelli' or 'Anti Machiavel', accused Machiavelli of being an atheist and accused politicians of his time by saying that his works were the "Koran of the courtiers", that "he is of no reputation in the court of France which hath not Machiavel's writings at the fingers ends" (Birely, The Counter Reformation, 1990).

Order-nr.: 60778