THE DISCOVERY OF THE ATOMIC NUCLEUS - THE RUTHERFORD ATOMIC MODEL.

RUTHERFORD, E. (ERNEST).

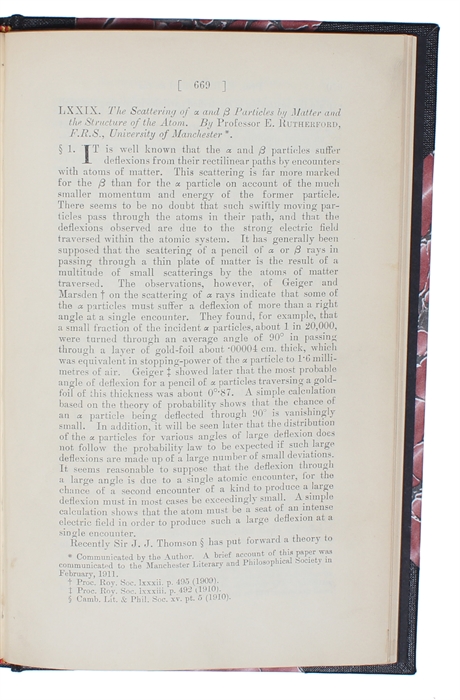

The Scattering of alpha and beta Particles by Matter and the Structure of the Atom.

(London, Taylor and Francis, 1911). 8vo . In recent half cloth with cloth title-label with gilt lettering to front board. Extracted from "The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science" Sixth Series, Vol. XXI. A fine and clean copy. [Rutherford's paper:] pp. 669-688. [Withbound:] Pp. 585-696.

First appearance of one of the most influential papers in physics in the 20th Century, describing the discovery of the ATOMIC NUCLEUS, and suggesting that the atom consists of a small central nucleus surrounded by electrons. This view of the atom is the one accepted today, and it replaced the concept of the featureless, indivisible spheres of Democritus, which dominated atomistic thinking for twenty-three centuries. Rutherford's 'nuclear atom' was a few years later by Niels Bohr, combined with the quantum theory of light to form the basis of his famous theory of the hydrogen atom.

Hans Geiger (Rutherford's assistant in his work on alpha particles) tells "One day (Rutherford) came into my room, obviously in the best of moods, and told me that now he knew what the atom looked like and what the strong scatterings signified." - On 7 March 1911, Rutherford presented his principal results to the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society. The definitive paper came out in the May issue of "Philosophical Magazine" (the paper offered here).

"After the first five or sic years of intense activity following the discovery of radioactivity, there was a brief lull untill 1911, when a new series of fundamental discoveries was made. These began with the discoveries of the nucleus and of artificial atomic transmutations by Rutherford. By 1811 it was known that electrons entered into the constitution of atoms, and Barkla had shown that each atom has approximately A/2 electrons (where A is the atomis weight). J.J.Thomson had conceived of a model of an atom according to which the electrons were distributed inside a positively charged sphere. To verify this hypothesis, Rutherford had the idea of bombarding matter using alpha-radiation of radioactive bodies and measuring the angles through which the rays were deflected as they passsed through matter. For the Thomson model of the atom the deflections should rarely be more than 1 or 2 degrees.However, Rutherford's experiments showed that deflections of more than 90 degrees could occur, particularly with heavy nuclei."(Taton (Edt.) Science in the Twentieth Century, p. 210).

Order-nr.: 57198