"MEN ARE BORN AND REMAIN FREE AND EQUAL IN RIGHTS"

[MOUNIER, MIRABEAU, DEMEUNIER, etc., etc.].

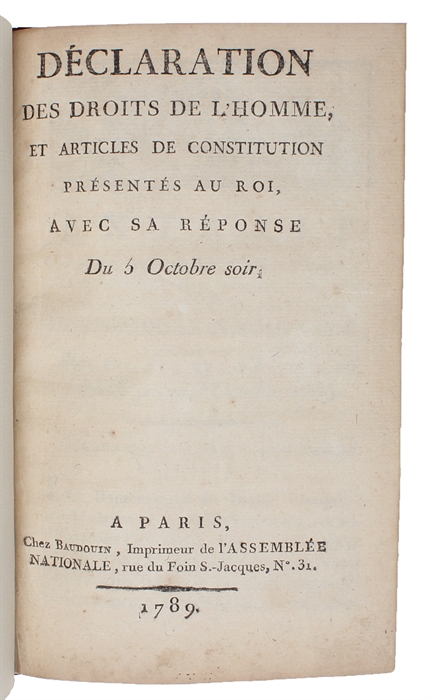

Déclaration des droits de l'Homme, et articles de Constitution présentés au roi, avec sa réponse du 5 Octobre soir. [Extrait des procês-verbaux de l'Assemblée Nationale, Des 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26 Aout & premier Octobre 1789. Déclaration des droits de l'homme en société + Extrait des procès-verbaux de l'Assemble Nationale, Des 9,11,12,14,17,21,24,27,30 Septembre et 1 Octobre 1789. Articles de Constitution].

Paris, Chez Baudouin, Imprimeur de l'Assamblée Nationale, 1789.

8vo. Bound in an exquisite later red half morocco with gilt spine. Top edge gilt. (1) f. (title-page), 8 pp. ("Déclaration des droits de l'Homme en société"), 6 pp. ("Articles de Constitution"), (1) f. ("Réponse du Roi"), (1) f. (blank). Woodcut head-pieces. Title-page slightly bowned, otherwise in excellent condition. A truly excellent copy.

The exceedingly scarce true first printing, in an incredibly rare form of off-print/separate printing, of one of the most important and influential documents in the history of mankind, namely the French Human Rights Declaration, containing also the articles for the first French Constitution. This groundbreaking publication constitutes a monumental change in the structure of the human world, providing all citizens with individual rights that we now take for granted.

This monument of humanist thought appeared in the "Procès verbal de l'Assemblée Nationale", copies of which are also very difficult to obtain. There, however, the two parts appeared without a title-page and without the final blank, which together constitute a form of wrappers for this off-print/separate printing, of which only five or six other copies are known and which is present in merely one or two libraries world-wide. As far as we now, only one other copy has been on the private market, and that did not have the blank back wrapper. This exceedingly rare separate printing of the Human Rights Declaration, with the Constitution, was intended for the inner circle of those participating in its creation and was limited to a very restricted number of copies - all of which will have been owned by the creators of the Declaration.

This epochal document is just as important today as it was when it was formulated during the French Revolution in 1789, and since 2003, the Declaration has been listed in the UNESCO Memory of World Register - "This fundamental legacy of the French Revolution formed the basis of the United Nations Declaration of 1948 and is of universal value". Few other documents in the history of mankind has done as much to determine the way we live and think, the way Western societies are structured and governed, and few other documents have had such a direct impact upon our constitutional rights and the way we view ourselves and others in society. It is here that we find the formulation of liberty and equality upon which so much of Western political and moral thought is based - that all "men are born and remain free and equal in rights" (Article 1), which were specified as the rights of liberty, private property, the inviolability of the person, and resistance to oppression (Article 2); that all citizens were equal before the law and were to have the right to participate in legislation directly or indirectly (Article 6); no one was to be arrested without a judicial order (Article 7); Freedom of religion (Article 10) and freedom of speech (Article 11) were safeguarded within the bounds of public "order" and "law", etc., etc.

The content of the document that were to change the Western world for good emerged largely from the ideals of the Enlightenment. "The sources of the Declaration included the major thinkers of the French Enlightenment, such as Montesquieu, who had urged the separation of powers, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who wrote of general will-the concept that the state represents the general will of the citizens. The idea that the individual must be safeguarded against arbitrary police or judicial action was anticipated by the 18th-century parlements, as well as by writers such as Voltaire. French jurists and economists such as the physiocrats had insisted on the inviolability of private property." (Encycl. Britt.).

The key drafts were prepared by Lafayette, working at times with Thomas Jefferson. In August 1789, Honoré Mirabeau played a central role in conceptualizing and drafting the Declaration. On August 26, 1789, in the midst of The French Revolution, the last article of the Declaration was adopted by the National Constituent Assembly, as the first step towards a constitution for France.

"In 1789 the people of France brought about the abolishment of the absolute monarchy and set the stage for the establishment of the first French Republic. Just six weeks after the storming of the Bastille, and barely three weeks after the abolition of feudalism, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (French: La Déclaration des Droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen) was adopted by the National Constituent Assembly as the first step toward writing a constitution for the Republic of France.

The Declaration proclaims that all citizens are to be guaranteed the rights of "liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression." It argues that the need for law derives from the fact that "...the exercise of the natural rights of each man has only those borders which assure other members of the society the enjoyment of these same rights." Thus, the Declaration sees law as an "expression of the general will," intended to promote this equality of rights and to forbid "only actions harmful to the society." (www.humanrights.com).

This sensational document became the crowning achievement of the French Revolution; it came to accelerate the overthrow of the "Ancien Régime" and sowed the seed of an extremely radical re-ordering of society. The Declaration interchanged the pre-revolutionary division of society -in the clergy, the aristocracy, and the common people- with a general equality - "All the citizens, being equal in [the eyes of the law], are equally admissible to all public dignities, places, and employments, according to their capacity and without distinction other than that of their virtues and of their talents" (From Article VI), upon which today's society is still based.

It is hard to imagine a work that is more important to the foundation of the society that we live in today.

Order-nr.: 57115