THE CORSAIR AFFAIR

KIERKEGAARD, SØREN.

1) Møller, P. L. Et Besøg i Soræ [in: Gæa. Æsthetisk Aarbog]. + 2) [Goldschmidt, Meïr Aaron, edt.]. Corsaren. Nr. 1-315. + 3) Frater Taciturnus: En omreisende Æsthetikers Virksomhed, og hvorledes han dog kom til at betale Gjæstebudet. [Printed in: Fædrelandet] + 4) Møller, P.L: Til Hr. Frater Taciturnus. [Printed in: Fædrelandet] + 5) Frater Taciturnus: Det dialektiske Resultat af en literair Politi=Forretning. [Printed in: Fædrelandet]

Kjøbenhavn, 1845-47.

1) 8vo. (IV), 372; (VIII),330; (VI),314 pp. Three volumes, all uncut and all in the original glitted paper bindings with gilding to boards. Rebacked and with restored tears to edges of boards. Inner hinges re-enforced. Gilding to boards rubbed and vague. Some brownspotting throughout. Illustrated.

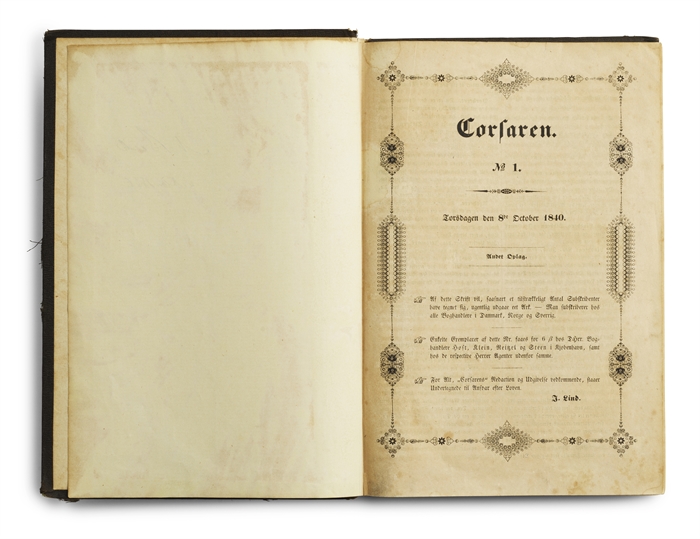

2) All that was issued of The Corsair during Goldschmidt’s ownership, including those of the seized issued that were not also destroyed: 36, 64, 70, 81, 293 as well as no. 215b, the addenda-issues to 75, 194, 215, 215b, 227, 259, 262, 208 as well as the extra numbers of 86 and 259 (with different dates and contents, i.e. just errors in the consecutive numbering), and “Følgeblad” after no. 204]. [The seized and destroyed issues are, as expected, not present: 3, 11, 21, 22, 26, 63, 65, 67, 68, 73, 77, 79, 80, 136, 149, 151, 176, 192, 194, 199, 208, 226, 242, 243, 261, 265, 270, 281, 294, 305, 307, 313]. Nos. 1-16: Andet Oplag (i.e. second issue). (Copenhagen), 1841-1846. Lex 8vo. Bound in three contemporary uniform black full cloth bindings with gilt lettering and numbering to spines. Extremities a bit worn and hinges a bit weak. Some brownspotting. Overall a very good set. Richly illustrated throughout, both in the text and with plates.

3) 6te Aarg. Nr. 2078. Løverdagen den 27. December 1845. 2 pp. Columns 16653-1660. Kierkegaard’s article: Columns 16653-16658

4) 6te Aarg. Nr. 2079. Mandagen den 29. December 1845. 2 pp. Columns 16661-16668. Møller’s article: Column 16665

5) 7de Aarg. Nr. 9. Løverdagen den 10. Januar. 1846. 2 pp. Columns 65-72. Kierkegaard’s article: Columns 65-68 (København), 1845 & 1846. All three articles in large 4to (33 x 24,7 and 33 x 24,5 cm). 2 columns to a page.

A magnificent set of all the original articles that cover the seminal Corsair Affair, which came to radically impact Kierkegaard's life - exceedingly scarce. To our knowledge, such a complete set of all the articles has never previously been for sale. The five numbers above together constitute all the seminal papers of the entire Corsair affair. As D. Anthony also puts it: “The summary of the affair is as follows. Other, lesser articles exist from this period, including some of unknown authorship… P.L. Møller’s article in Gæa entitled «A Visit in Søro» Kierkegaard responds in this article, “The Activity Of A Traveling Esthetician” P.L. Møller’s reply in The Fatherland Goldschmidt’s first Corsair article Kierkegaard’s second and final reply, “The Dialectical Result of a Literary Police Action” A string of articles published in The Corsair” This set includes 1) The first edition of all three volumes of Gæa (all that was published), the aesthetical magazine by P.L. Møller, in which he published his review of Kierkegaard’s Stages on Life’s Way, which is the paper that begins the entire Corsair Affair, the paper, which Kierkegaard responds to in The Fatherland, at the same time attacking The Corsair. Apart from Møller’s fateful review of Stages on Life’s Way, which in turn came to have such a profound influence upon Kierkegaard’s life, the literary periodical also contains numerous original contributions by Kierkegaard’s most famous contemporaries, providing an excellent picture of Danish literature at this exact moment in time. There are numerous contributions by Hans Christian Andersen: Stoppenaalen (BFN 482), three poems for Jenny Lind, Melbye, and Gertner respectively (BFN 483, 484, 485), To Billeder fra Kjøbenhavn (BFN 515, 513), and Hvad den lille Hund siger (BFN 514); Blicher: Pilen (Bertelsen s. 42), Halv Spansk og halv Dansk (Bertelsen s. 42), and Ungdom og Løndom (Bertelsen s. 42) and many more first printings by Aarestup, H.C. Ørsted, Oehlenschläger, Christian Winther, Hauch, Høegh-Guldberg, P. L. Møller himself, and many others. 2) A complete collection of all rightful issues of Goldschmidt’s Corsaren, the seminal periodical that took Copenhagen by storm and is now famous world-wide for its harsh ridicule of Søren Kierkegaard, with the iconic caricature of him that now constitutes the most famous “portrait” of the founder of Existentialism. The seized numbers account for the lacunae in the numbering of the issues in the present set. Most of these were destroyed and never reached the public, to the great disappointment of the many loyal readers. A few of the seized issues were later released by the chancellery, and the subscribers would receive them, albeit several months later. This accounts for the five issues that are present here, although they were seized – the few seized issues that were not also destroyed. 3)-5) The exceedingly scarce original printing of the three issues of Fædrelandet that contain the three articles in this paper pertaining to The Corsair Affair – Kierkegaard’s two only published contributions to the Corsair Affair as well as Møller’s important reply published merely two days after Kierkegaard’s first. As we know, a defining moment in Kierkegaard’s life was his engagement – and not least the termination of it – to Regine Olsen. This would affect him, his writings, and his thoughts for the rest of his life. The next defining moment that would also leave deep traces in Kierkegaard’s work, mental state, and thought, was that of the so-called Corsair Affair, which evolved into the greatest literary battle in Danish history. It had enormous consequences for everyone involved, not least Kierkegaard, who would never really recover from it. The Corsair was one of the most important periodicals in the history of Denmark. With its witty disposition, lack of respect for everyone and everything, and its founder’s awe of the French Revolution and republican ideas, The Corsair became the first periodical of its kind in Denmark. It invoked an entirely new genre, founded Danish political satire, and would prove groundbreaking in several respects. It was not only political and meant to be an “Organ for and sculpting of the mass opinion”, but it also viewed as its goal “to assert and cherish the purity and dignity of literature” (Bredsdorff p. 28). The first issue of The Corsair saw the light of day on October 8, 1840. The periodical was founded and owned by Meïr Aaron Goldschmidt who was also the actual editor and the author of the greater part of the writings in it. In 1846, Goldschmidt sold the periodical, and although it continued its existence until 1855, it almost immediately lost the significance it had when Goldschmidt owned it. The essence of the periodical thus counts the numbers 1 (from October 8, 1840) to 315 (October 2, 1846). Apart from its political stance and the great effect The Corsair came to have upon the shaping of Danish politics during the years that Goldschmidt ran it, the periodical is now primarily associated with one towering “event” known as the “Corsair Affair” – the strife that emerged between the widest read and most influential periodical of the time and the person that would prove to be the greatest thinker that emerged from Danish soil, Søren Kierkegaard. Goldschmidt and Kierkegaard had met each other for the first time right after the appearance of Kierkegaard’s first book, in 1838 and were not ill disposed towards each other. As we know, Goldschmidt had founded The Corsair in 1840, and Kierkegaard published his dissertation, On the Concept of Irony, in 1840. On October 8, 1841 (no. 49), the contents of the dissertation were briefly mentioned in The Corsair, and the actual review followed in no. 51 (October 22). The review was not bad, there was no real mockery, and Goldschmidt even deemed it “interesting”. Like everyone else in Copenhagen at the time, Kierkegaard by now also knew the identity of the true editor of The Corsair, and when he met Goldschmidt again, coincidentally this time, he mentioned to him that he had no reason to be dissatisfied with the review, but that it lacked “composition”, and that Goldschmidt ought to generally “pursue comical composition”. In February 1843, Kierkegaard’s magnum opus, Either-Or, appeared. Goldschmidt read it and was immediately infatuated by it. There was no end to his appreciation of this masterpiece. He reviews it in The Corsair, no. 129, March 10, 1843, where he states “This author is a mighty intellectual, he is an intellectual aristocrat, he mocks the entire human race, portrays its wretchedness; but he is entitled thereto, he is an unusual intellect.” And this is not the only time that Goldschmidt praises Kierkegaard. One would think that Kierkegaard would have been thrilled with this. Usually, he is portrayed as a misunderstood, struggling author, who no-one really believed in and who was only vindicated after his death. But here, he is so highly praised, for his early works no less, by one of the most influential men in the country at the time. But Kierkegaard was not pleased. He might have felt left out for not being made fun of like everyone else in The Corsair, and he was definitely not in agreement with Goldschmidt politically. Kierkegaard was a true conservative and did not appreciate the horrible liberal radicalism of The Corsair. It clearly bothered him to be lauded by this “gossip rag”. When The Corsair once again highlighted the immortality of Victor Eremita (Kierkegaard’s pseudonym) in a review of a novel by Carsten Hauch, the praise seems to have become too much for the conservative Kierkegaard. In a letter (that he never sent, though), he writes to The Corsair, in the satirical manner of the periodical itself “kill me, but do not make me immortal!”... “Oh! This gruesome mercy and to be spared, forever designated a non-human, because The Corsair inhumanely spared him!... Oh! Let you be moved to pity, stop with your sublime gruesome mercy, kill me like everyone else!”, asking to be ridiculed by The Corsair like everyone else. The defining moment came, when at the end of December 1845, Kierkegaard writes an article in the paper The Fatherland, under the pseudonym of Frater Taciturnus. This paper is Kierkegaard’s first of two written contributions to the Corsair Affair and the one that set it off. The paper entitled “The Activity of a Traveling Esthetician and How He Still Happened to Pay for the Dinner” was written as a reaction to P.L. Møller’s essay “A Visit in Sorø”, which Møller had published in his aesthetic yearbook Gæa on December 22nd, 1845 (Gæa for the year 1846). Here, Møller criticizes Kierkegaard’s Stages on Life’s Way. It is also implied in the title that the “Visit in Sorø”, during which the conversation about Stages on Life’s Way took place, was at the home of Hauch, who lived in Sorø. Kierkegaard replies with this fateful paper, written in five days, over Christmas, and published in The Fatherland on December 27, 1845. Here, Kierkegaard not only reacts to the implication that Hauch was present in the critique of his Stages on Life’s Way and to Møller’s general critique of it, he also publicly regrets not being ridiculed in The Corsair, and he implies that P.L. Møller (whom he despised) is the true editor of The Corsair. There is no doubt that Kierkegaard wished to discredit Møller, who he considered opportunistic (Møller was seeking a chair at the university while secretly publishing his articles in The Corsair), and he succeeded. Kierkegaard’s paper was devastating for Møller and effectually meant the end of his career. Møller had stood in for Goldschmidt during Goldschmidt’s impeachment (accused of being the editor of The Corsair), which he had done as a favour to Goldschmidt, but he was not otherwise truly involved with the “dangerous” periodical. Møller replies a mere two days later, with a small article For Mr. Frater Taciturnus in The Fatherland on December 29th, 1845. Here, he thanks Kierkegaard for having responded so swiftly to his article in Gæa, but immediately objecting that Kierkegaard must accept being criticized and that the only way of avoiding criticism altogether would be not to publish anything. He does not engage in further discussion of Kierkegaard’s critique, but he denies Kierkegaard’s assumption that the conversation about Stages on Life’s Way that took place in Sorø took place at Hauch’s house and claims that the mentioned dinner party was purely f ictitious. Møller refrains from commenting on the assumptions about Møller’s involvement in The Corsair. The Corsair does not, however. As of 1846, everything changed. Goldschmidt began ridiculing Kierkegaard in The Corsair, and he did not tread lightly. The first polemic against him is to be found in no. 276 (January 2), where Kierkegaard’s “unveiling” of Møller is ridiculed. The following issue, no. 277 (January 9) contains the first of many caricature drawings of Kierkegaard, defining the way that Kierkegaard came to be viewed ever after. The drawing was done by the house illustrator of The Corsair, Klæstrup, and has gone down in history as THE most important depiction of Søren Kierkegaard ever. The moment it appeared – January 9, 1846 – became a defining moment in the life of the founder of Existentialism. Not only was he depicted in a ridiculous way, caricatured so that everyone knew who it was, a devastating polemical description of his appearance – for instance mentioning one trouser leg being shorter than the other – also followed. This one issue of The Corsair began the Copenhagen “trend” of discussing the trousers of Kierkegaard – a “trend” that became so bothersome for Kierkegaard that he never really recovered from general ridicule. The Corsair had thus begun the momentous ridicule of Kierkegaard’s outer appearance that came to hurt him so deeply. The Corsair continued mocking Kierkegaard in no. 277, pointing also to the fact that he was not the keeper of secrets; Kierkegaard now replied through The Fatherland, again under the name Frater Taciturnus, with a paper entitled Det dialektiske resultat af en literair Politi-Forretning, published on January 10th, 1846. In this paper, Kierkegaard’s second and final published contribution to the Corsair Affair, he exposes The Corsair as a gossip rag and points to the fact that he had “ordered” the ridicule of him, poking fun at the unserious magazine. Again, he asks to be abused in the pages of The Corsair and says that he will not suffer being praised by such a paper. “As it turned out, The Corsair was all too happy to oblige and sustained his request for months to such an extent that Kierkegaard refrained himself from further public response in the matter. We do, however, get a glimpse of his reaction and mood from the numerous journal entries during this time.” (D. Anthony). The Corsair continued to retaliate, continued to mock and ridicule Kierkegaard, and continued bringing caricatures of him – in numbers 278, 279, 280. In no. 284, Goldschmidt once again praises Kierkegaard, reviewing his brilliant philosophical magnum opus Concluding Unscientific Postscript, and although the following months of The Corsair contain several harsh polemics against Kierkegaard, which were devastating to the selfconscious philosopher, Goldschmidt says that the defining moment that made him give up the magazine and sell it, came when, after the publication of Concluding Unscientific Postscript, he met Kierkegaard on the street, which he had done so often, and Kierkegaard refused to greet him. In Concluding Unscientific Postscript, Kierkegaard admits to being the author of all the pseudonymous writings, which is another defining moment in his career. This prompted another caricature in The Corsair – in no. 285 from March 6 1846, Kierkegaard is famously depicted as the centre of the universe. Also in numbers 297, 299, 300, and 304, The Corsair polemicizes against Kierkegaard. The caricatures were devastating to Kierkegaard, who keeps mentioning the polemics in his diaries. He so wishes that The Corsair would now stop the mocking and let him be. The extent to which his trousers and his appearance in general had become a subject of gossip for the inhabitants of Copenhagen was almost unbearable to him. “I need only put on my trousers, and all eyes are on me, on my trousers”, he writes, and elsewhere, after talking about the vast general ridicule from the Copenhagen public, “such knowing mistreatment is one of the most painful things. Everything else comes to an end, but not this. To sit in a church and then a couple of ruffians have the audacity to sit next to one only to constantly ogle one’s trousers and mock one in a conversation that is so loud that one hears every single word.” (Pap. VIII: 1A, 99). The mocking would take no end, and Kierkegaard’s private papers are full of examples of how he was made fun of and how everyone in Copenhagen would laugh at him and his trousers. “What Goldschmidt and P.L. Møller practice in the large, every individual practices in the small.” (Ibid., 218). The effect of the caricatures was grueling, and Kierkegaard never really recovered from it. With its political stance and its provocative manner, it is no wonder that many issues of the groundbreaking periodical were seized, forbidden, and destroyed by the police censure, which accounts for lacunae in the numbering of the issues. This also accounts for the long list of fictional names of editors. Goldschmidt is never actually mentioned as the editor anywhere in the periodical, and, in the beginning, every time a number is seized, a new fictional editor-name appears on the following issues. Already issue no. 3 was confiscated, and during Goldschmidt’s ownership, 40 issues were seized and forbidden. Within the first 26 weeks of its existence, The Corsair had officially had no less than six different editors in chief. In the six years that Goldschmidt owned it, 14 different editor-names appear. The first issue of The Corsair took Copenhagen by storm; it was eagerly read and discussed, and there were countless rumors as to who the real editor/editors was/were. Issue no. 1 was sold out so quickly that a second issue of it followed almost immediately. Thus, often in the rare sets one encounters of The Corsair, the early issues will be in second issue, as it was only later on that the editor realized the need to print in larger numbers. Himmelstrup: 81, 88 & 89.

Order-nr.: 62945

![1) Møller, P. L. Et Besøg i Soræ [in: Gæa. Æsthetisk Aarbog]. +

2) [Goldschmidt, Meïr Aaron, edt.]. Corsaren. Nr. 1-315. +

3) Frater Taciturnus: En omreisende Æsthetikers Virksomhed,

og hvorledes han dog kom til at betale Gjæstebudet. [Printed in: F...](/images/product/62945b.jpg)

![1) Møller, P. L. Et Besøg i Soræ [in: Gæa. Æsthetisk Aarbog]. +

2) [Goldschmidt, Meïr Aaron, edt.]. Corsaren. Nr. 1-315. +

3) Frater Taciturnus: En omreisende Æsthetikers Virksomhed,

og hvorledes han dog kom til at betale Gjæstebudet. [Printed in: F...](/images/product/62945c.jpg)

![1) Møller, P. L. Et Besøg i Soræ [in: Gæa. Æsthetisk Aarbog]. +

2) [Goldschmidt, Meïr Aaron, edt.]. Corsaren. Nr. 1-315. +

3) Frater Taciturnus: En omreisende Æsthetikers Virksomhed,

og hvorledes han dog kom til at betale Gjæstebudet. [Printed in: F...](/images/product/62945d.jpg)

![1) Møller, P. L. Et Besøg i Soræ [in: Gæa. Æsthetisk Aarbog]. +

2) [Goldschmidt, Meïr Aaron, edt.]. Corsaren. Nr. 1-315. +

3) Frater Taciturnus: En omreisende Æsthetikers Virksomhed,

og hvorledes han dog kom til at betale Gjæstebudet. [Printed in: F...](/images/product/62945e.jpg)

![1) Møller, P. L. Et Besøg i Soræ [in: Gæa. Æsthetisk Aarbog]. +

2) [Goldschmidt, Meïr Aaron, edt.]. Corsaren. Nr. 1-315. +

3) Frater Taciturnus: En omreisende Æsthetikers Virksomhed,

og hvorledes han dog kom til at betale Gjæstebudet. [Printed in: F...](/images/product/62945f.jpg)

![1) Møller, P. L. Et Besøg i Soræ [in: Gæa. Æsthetisk Aarbog]. +

2) [Goldschmidt, Meïr Aaron, edt.]. Corsaren. Nr. 1-315. +

3) Frater Taciturnus: En omreisende Æsthetikers Virksomhed,

og hvorledes han dog kom til at betale Gjæstebudet. [Printed in: F...](/images/product/62945g.jpg)