THE GREATEST EDITION OF ARISTOTLE'S POETICS

VITTORE, PIETRO (or Piero) (Lat. PETRUS VICTORIUS). [ARISTOTELES - ARISTOTLE].

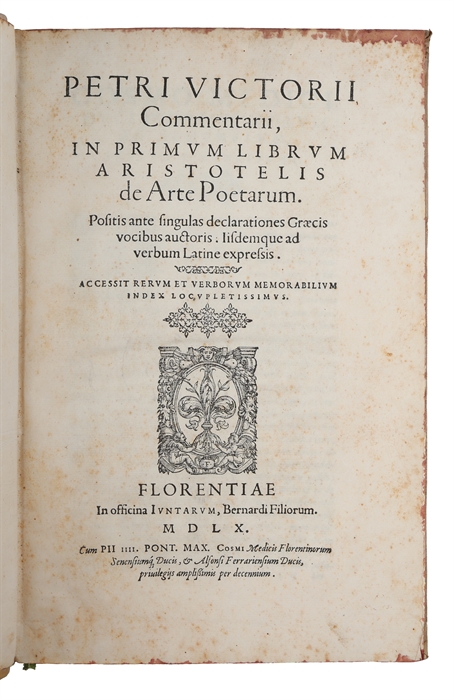

Commentarii, in primum librum Aristotelis de Arte Poetarum. Positis singulas declarationes Graecis auctoris. Iisdemque ad verbum Latine expressis. Acessit rerum et verborum memorabiblium index locupletissimus.

Florence, In officina Iuntaru, Barnardi Filiorum, 1560.

Small folio. 18th century full vellum with gilt labels to spine. Wear to capitals and small worm tracts towrad opper hinges. Corners a bit bumped. A very nice and sturdy binding. Marbled edges. Some browspotting throughout. Small wormholes to blank margin of final leaf, far from affecting imprint. Woodcut vignette to title-page and to verso of colophon-leaf. (10), 308, (12) ff.

The rare first edition of Vittore's main work, his great edition, translation, and commentary on Aristotle's Poetics, which is arguably the most important and influential commentary on the work ever published, profoundly shaping our understanding and interpretation of Aristotelian literary theory. Petrus Victorius (or Piero/ Pietro Vittore/Vettore) (1499-1584) is not only the “first great editor of the Poetics” (McMahon), he is also considered "the greatest Greek scholar of Italy" (Whibley), “the leading Italian scholar of his time” (Encycl. Britt.), “the last great figure [from that period] in the domain of Greek studies” (Willamowitz), and “the foremost representative of classical scholarship in [Italy] during the sixteenth century, which, for Italy at least, may well be called the “saeculum Victorianum”.” (Sandys). His magnum opus and without doubt most influential work is his edition with commentary of Aristotle’s Poetics, which is of seminal importance in several respects. It is crucial to our understanding of Aristotle’s great work, shaping the way that all later scholars have read it. The understanding of Aristotle’s work on poetry came to define the way that we have understood literature and fiction ever since the Renaissance, and Victorius is the leading interpreter. ““From the sixteenth century to Romanticism, European literary theory used the term marvel or wonder (It. meraviglia, ammirabile, Fr. merveille, Sp. maravilla) to designate everything that was on the conceptual margins of the poetics of probability and imitation. The discovery and complete reception of Aristotle’s Poetics between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries resulted in the dissemination of an idea of poetry as the imitation of the actions of men, whose main part was the plot, or the structuring of actions ordered according to the laws of necessity, credibility and probability. This formed the basis of Neo-Aristotelian poetics, which determined the ways of thinking about literature and fiction for more than four centuries.” (Vega p. 280). Especially the idea of “wonder” in Aristotle’s Poetics came to be one of the founding ideas of modern literary theory. And especially here, Victurius’ reading is groundbreaking, playing a central part in the reception and understanding of the work over the centuries to come. “A single editorial decision in just one passage (and what is more, in a complex, fragmentary, unfinished text like the Poetics) affects the entire work…” (Vega, p. 284). “The text of the Poetics that can be read in the editions and translations of the sixteenth century and a large part of the seventeenth (with one exception, as we shall see [NB. This exception is Victorius] ) does not include the term alogon in the passage that deals with wonder. It does not appear in the first Greek edition, the famous Aldine princeps of 1508, or in the Latin translations of the end of the fifteenth century; it is not in the edition and translation by Alexander Paccius or Pazzi, the one most widely read in the sixteenth century, neither does it appear in the edition with commentary by Francesco Robortello, nor in Vincenzo Maggi’s Enarrationes, nor in the vernacular commentaries of Ludovico Castelvetro and Alessandro Piccolomini. What is more, a detailed revision of the history of the text reveals that no manuscript of the Poetics and no direct or indirect testimonies (not even in the Arabic branch of its transmission) have ever included the term alogon.” (Vega, p. 282). It is Victorius, who is solely responsible for the reading that is generally accepted today as well. “The moment when the idea of irrationality [alogon] appears for the first time in Aristotle’s text can be identified without hesitation as 1560, which is the date when the edition, translation and commentary on the Poetics by the philologist and Hellenist Pier Vettori, or Victorius, was printed on the presses of Giunti in Florence. Vettori is the one who first edits alogon, even though no testimony provides him with this reading, and he does so fully aware of his choice and its implications” (Vega, pp. 287-89). “The success of Victorius’ reading, while not immediate, was extraordinary.” (Vega, p. 287) Antonio Viperano accepts the reading “alogon”, with all it involves (De poetica libri tres), Ricciboni adapts it in his edition of Aristotle’s Poetics, Tasso embraces it (Discorsi dell’arte poetica, Discorsi del poema eroico), and it is implicit in Alonso López Pinciano’s Philosophia Antigua Poetica. Vossius in 17th century Germany makes abundant glosses on alogon in his books on poetics, and the commentators and translators of the “Poetics” in France preferred Victorius’ reading in every case. “Victorius’ conjecture seems to have convinced all editors and commentators, who reproduce it without question in every case.” (Vega, p. 289). The influence of Victorius’ interpretation of Aristotelian literary theory that he presented in his magnum opus (i.e. the present work) was not limited to the use of specific words that changed the reception history of Aristotle’s Poetics. His entire view of poetry through an interpretation of Aristotle was highly original and came to define the way we understand literature in general. Victorius was one of the first to put forth the belief that heroic poetry should present a Platonic idea of perfect virtue, contributing to the centuries long doctrine of the perfect hero as perfect exemplar, and he was one of the first to revive Aristotle’s idea of purgation from tragedy (still widespread today) and to also understand the existence of a purgation from poetry. “He viewed poetry as a moderator of minds “By reading poetry men “become moderate in temper and their turbid motions are extinguished.” Poems “purge our minds of blemish and spot”. Vettori realized that Aristotle’s reference to catharsis should be applied to tragedy alone, but he added that similar purgations could be achieved by other kinds of poetry, effective, however on other passions than pity and fear and with the aid of other instruments.” (Hathaway pp. 292-93). Apart from his overall interpretation of Aristotle’s literary theory and his groundbreaking reading of the most central passages of the Poetics, Victorius was also the first to determine that the Aristotelian text that has come down to us is not complete. “Victorius was the first to see that the treatise now known as the Poetics is only the surviving portion of a larger work.” (Bywater, p. XX). “during his lifetime five medals were struck in his [i.e. Victorius’] honour, and his portrait was painted by Titian… His fame was not limited to his own land, or his own time. His scrupulous care and unwearied industry are lauded by Turnebus, who declines to be compared with him, even for a moment; the epiteths doctissiums, optimus, and fidelissimus are applied to him by the younger and the greater of the two Scaligers, while Muretus calls him eruditorum coryphaeus; and similar eulogies might be quoted from Justus Lipsius,.. Dacius, … and Graevius. He is described as having climbed the “hill of virtue”, and taken his place on its summit between Cicero and Aristotle. In his funeral oration, Salviati says of him, in the personification of Italia: “Now no more shall distant peoples cross the snows of the Alps to see Victorius, or men of mark arrive from every land to hear him; or princes hold converse with him. Now no more shall the works of scholars in all parts of the world be sent here for his approval; or youth learn wisdom from his lips.” (Sandys, pp. 139-40). “[N]o one, said a contemporary of his in a funerary laudatio, ‘left Aristotle in a cleaner state (purgatior)’.” (Baldi). _____________________________________________ Adams: 1905; Brunet V: 1179; Graesse I: 213 (”édition excellente quant à la critique” and noting that some copies bear the dates 1563 and 1564). Sandys: A History of Classical Scholarship Vol. II, 2003, pp. 135-140. Hathaway, Baxter: The Age of Criticism: The Late Renaissance in Italy. Cornell University Press, 1962. A.Philip McMahon: On the Second Book of Aristotle's Poetics and the Source of Theophrastus' Definition of Tragedy Author(s). In: Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, 1917, Vol. 28 (1917), pp. 1-46. Christopher Rowe: Petrus Victorius and Aristotle’s Eudemian Ethics, Cambridge University Press online, 2025. Vega, Maria José: Wonder and the Irrational. The Invention of Aristotle’s Poetics in the Sixteenth Century. In: Nous, Polis, Nomos... (Berlin, Academia Verlag, 2016). Baldi: Il greco a Firenze e Pier Vettori (1499–1585), (Alessandria, 2014), 117.

Order-nr.: 62508